Introduction to the AIDS Education Poster Collection at the University of Rochester Department of Rare Books, Special Collections, & Preservation

--Alexander Brier Marr (UR, Visual and Cultural Studies PhD student)

2011 marks the thirtieth anniversary of the first diagnosis of what would come to be known as Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome (AIDS) by University of Rochester alumni Dr. Michael S. Gottlieb. Since then the disease has proliferated, challenging the expertise of scientists and doctors struggling to understand and contain it. Not only has it expanded beyond the community of gay American men in which Gottlieb identified the virus, but it has also required responders to think beyond the limits of medical knowledge. Discourse on AIDS arises in art history classrooms, Haitian field hospitals, and conference rooms in U.N. offices.

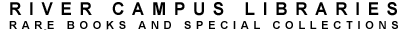

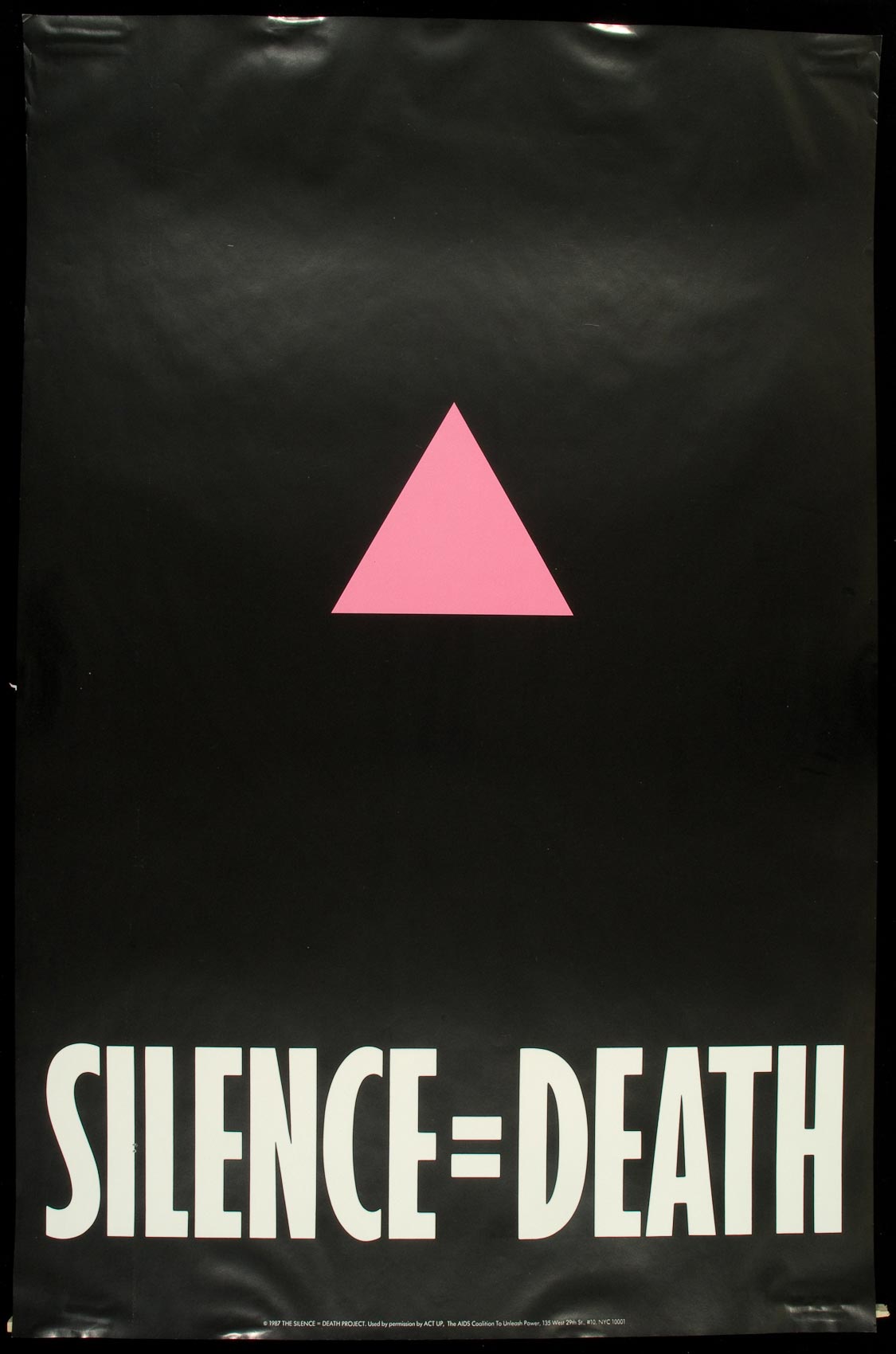

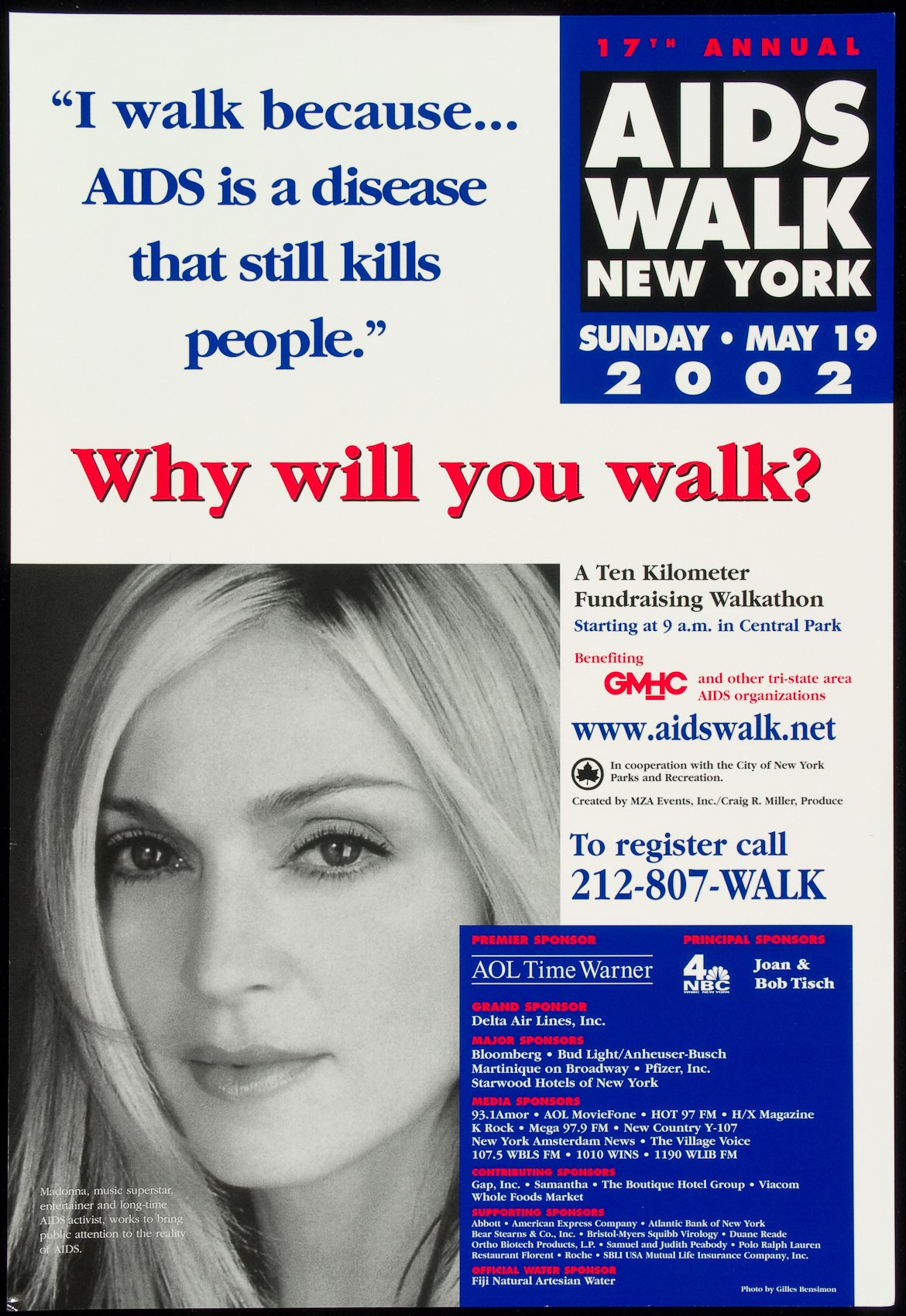

As a visual history of the first three decades of the AIDS crisis, the AIDS Education Poster Collection (AEPC) at the Department of Rare Books, Special Collections, & Preservation at the University of Rochester contains over 6200 posters from over 100 countries in more than 60 languages. It is the largest single collection of AIDS visual resources. The AEPC chronicles the look of AIDS around the world at various moments. Each entry includes information regarding its year of publication and its sponsoring organization. Contact information for sponsoring organizations often accompanies posters in the database. The entire collection will be available here in digital form. Highlights include a rich assortment of posters and pamphlets from Gran Fury/ACT UP [fig. 1], the slickly photographed “STOP AIDS” posters produced by advertising agency cR Basel for the Swiss Ministry of Health [fig. 2], the highly successful hand-drawn informational broadsheets used in Uganda [fig. 3], and a host of American posters and flyers from the last ten years that implore viewers to remember the ravages of an increasingly invisible epidemic [fig. 4].

|

|

|

|

|

|

Figure 1 |

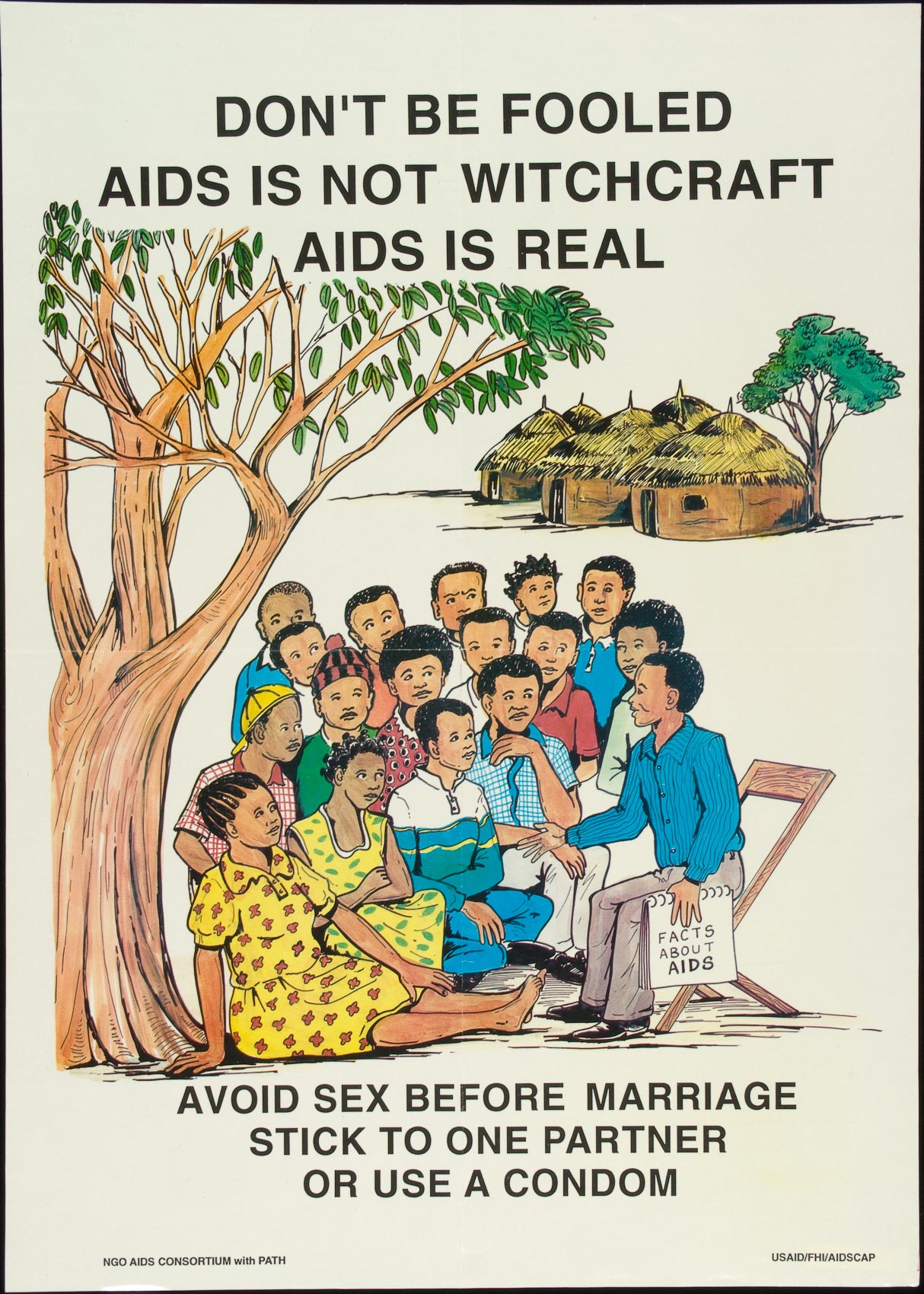

Figure 2 |

Figure 3 |

Figure 4 |

The database is especially useful for scholars and students of medical history, visual culture, communication and media, and public health. Specialists in the society and culture of various countries will also find the AEPC helpful. That said, the database may be of limited use to researchers interested in sites of display, number of posters in a series, and the circulation of posters. Despite the wide scope of the AEPC, it selectively represents global visual culture of HIV/AIDS. A single collector, Dr. Edward Atwater, amassed the AEPC through his correspondences and travels around the world.

HIV is a global virus that demands an interdisciplinary response. A traditional medical approach focuses on patient behavior (intravenous drug use, unprotected sex) and research on how the virus affects discrete bodies. The posters in the AEPC have been used by governmental and non-governmental organizations the world over to make medical information known. Posters distributed by the WHO and UNAIDS are well represented in the collection, as are informational posters sponsored by national governments. Yet posters cannot communicate medical information without addressing local assumptions about morality and sexuality. In some cases posters mobilize established moral codes to advocate for HIV/AIDS awareness. In other cases, as with a poster sponsored by the Kenya National AIDS Control Programme in 2000, posters pit “facts about AIDS” against local, non-scientific belief systems [fig. 5].

HIV is a global virus that demands an interdisciplinary response. A traditional medical approach focuses on patient behavior (intravenous drug use, unprotected sex) and research on how the virus affects discrete bodies. The posters in the AEPC have been used by governmental and non-governmental organizations the world over to make medical information known. Posters distributed by the WHO and UNAIDS are well represented in the collection, as are informational posters sponsored by national governments. Yet posters cannot communicate medical information without addressing local assumptions about morality and sexuality. In some cases posters mobilize established moral codes to advocate for HIV/AIDS awareness. In other cases, as with a poster sponsored by the Kenya National AIDS Control Programme in 2000, posters pit “facts about AIDS” against local, non-scientific belief systems [fig. 5].

♦ ♦ ♦ ♦

Scholars in the humanities have primarily examined two social dimensions of AIDS: how it develops a picture of others and how people exchange it through networks determined by shared beliefs and behaviors. First, we cannot respond to HIV/AIDS without considering how it engenders and reinforces socially embedded perceptions of others. In the 1980s, a wild fear of contamination through touch and a perception of gay men as marginal inhibited a federal response. AIDS frequently stirs up two stereotypes: gay men as licentious and amoral and Sub-Saharan Africans as pre-modern. Rarely have medical urgencies hinged this acutely on understanding the politics of representation. Second, the way that AIDS is transmitted in Uganda is different from the way it moves in Thailand or Northern Europe. In a comparative study of AIDS in South Africa and Uganda, for example, the anthropologist Robert Thornton argues that culture—rather than personal behavior—regulates the spread of HIV.[1] These two social aspects of the disease, its capacity to mediate a picture of others and its transmission, are linked. There truly is a network of transmission and treatment, but it cannot exist without a twin network of representations. The AEPC traces this network. Dr. Gottlieb’s discovery was the first warning sign of an epidemic vaster than he could have imagined. At the time he suggested that it was “possibly a bigger story than Legionnaire’s disease.”[2] It turned out to be much larger than that, indeed. In 1987 Douglas Crimp (Fanny Knapp Allen Professor of Art History and Professor of Visual and Cultural Studies at the University of Rochester) edited “AIDS: Cultural Analysis/Cultural Activism,” a special issue of the art history journal October, an early contribution to the culturally-minded study of AIDS. For the next fifteen years Crimp would develop one of the most significant non-medical interpretations of AIDS, arguing that politics of representation lie at the heart of an ostensibly scientific and medical problem. “AIDS does not exist apart from the practices that conceptualize it, represent it, and respond to it.”[3] Only by first understanding this relation between AIDS and representation, Crimp argued, can we effectively respond to and control the disease. Crimp wrote primarily about activist art made by gay men in New York City, though his argument has proven prescient and remarkably useful to scholarship on a range of HIV-positive groups. Antiretroviral medication makes the disease less visible in the post-industrial world. Medical successes put us in danger of forgetting that this disease is the most lethal in the world. As anthropologist Jean Comaroff writes, “We may lack the nerve or imagination to theorize it [AIDS] adequately, but it has certainly been theorizing us for quite a while.”[4] It lays bare global distributions of wealth, the status of the nation state, the strength of private health organizations, and perceptions of science at the beginning of the twenty-first century. The disease is only understandable through representation. And those representations, made available by the AEPC, help bring to light cultural differences and shifting global relations. The disease can only be dealt with in so far as it exists in various systems of knowing (Ugandan, South African, queer, medical, feminine). Instead of merely conceiving of AIDS as a number of primary cases followed by medical and political responses, it is valuable to understand the global epidemic as a series of pictures. Virus and representation constitute each other. The AEPC charts not just the history of visual responses to AIDS/HIV, but the history of the disease itself.

[1] Robert J. Thornton, Unimagined Community: Sex, Networks, and AIDS in Uganda and South Africa (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 2008).

[2] Gottlieb, Morbidity and Mortality Report, June 5, 1981. (http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/PDF/wk/mm4534.pdf)

[3] Douglas Crimp, “AIDS: Cultural Analysis/Cultural Activism,” in Melancholia and Moralism (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2002), 28 (originally published as the introduction to October 43 (Winter 1987)).

[4] Jean Comaroff, “Beyond Bare Life: AIDS, (Bio)Politics, and the Neoliberal Order,” Public Culture 19.1 (2007), 198.